Lakota Orthography Reclamation

“It is time the Lak̇ot̄a language returns as a vehicle of empowerment.”- Albert White Hat, Reading and Writing the Lakota Language.

So the other day I was looking up things for the Lak̇ot̄a Iyap̄i Ok̇olak̄iċiye Orthography, often referred to as the White Hat orthography and stumbled upon a post in my search results by an admin on the lakotadictionary.org website. This website is run by the Lakota Language Consortium. Although I do not know who wrote this post other than that they are an admin for the site that went by the name nahomnikhiye, it does really sum up much of the talking points and propaganda we’ve been fed over the years for the New Lakota Dictionary Orthography popularized by the Lakota Language Consortium so I wanted to respond to it here.

For those not in the know, orthography has been a big fight amongst us Lakota since the (non-) Lakota Language Consortium started to insert themselves on us starting in the early 2000’s and continuing into the now. One of their big issues is the way we write our language. The founders of this consortium- Austrian Anthropologist, Wilhelm Meya (Coleman, 2013), and the Czech Hobbyist Linguist who refers to himself as Crazy Buffalo, otherwise known as Jan Ullrich, have made all out marketing and propaganda pushes through the years to force their writing system on the Lakota people. (This is why I call them the non-Lakota Language Consortium). Many of the younger Lakota language teachers now parrot these talking points without much thought as I once did in the past. After all the intrusion and propaganda and belief that this is a settled issue, there is now a call from their language warriors for all of us to “stop fighting” and to conveniently forget how we all got here. I contend however that we are not fighting, we are reclaiming. We are reclaiming our language and part of this reclamation is reclaiming the way we chose to write our oral language.

Much of the argument put forth by the LLC for their orthography is a lot of opinion and preference in an effort to sell more of their products back to us, the Lakota people. In their orthography video (which is basically the post below strung out over a 15 minute period), History of Lakota Orthography, they make it a point to let everyone know that they never copyrighted their orthography. (They do take a dig at the White Hat Orthography or his book Reading and Writing the Lakota Language without the courage of naming Albert or the elders he worked with which doesn’t surprise me). This perked my ears, the claim of never copyrighting their orthography, because this makes me think that they are very aware of what they are doing in regards to their copyrighting of other things, like their dictionary and grammar book. For more info on this please read my previous blog, Ochethi Shakowin Data Sovereignty. Their whole video is basically to pedal their products which they do at the end.

The reason I bring this up though is that they have created a system of dependence. Their writing system leads to their products and their products to their orthography. I compare it to the old factories who would give their workers company currency that is accepted only at their factory stores to continue to feed the monster. You want to look up a word in their dictionary? You better know how to write it in their orthography. Their orthography points to their resources and their resources back to their orthography.

I recently ran across a phrase popularized by a Canadian communication theorist, Marshall McLuhan, “The medium is the message.” This hit me between my eyes in regards to orthography. I couldn’t help myself in thinking, what are we saying by the orthography (the medium) we use (and not even necessarily what we are saying)? Especially when there are already beautiful orthographies that have been created by Lakota/Dakota speakers?

Some examples; Lak̇ot̄a Iyap̄i Ok̇olak̄iċiye orthography- created by many elders, teachers, and speakers often referred to as the White Hat Orthography and the official orthography of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, Lakota Sounds by longtime Lakota Teacher and First language speaker- Karen White Butterfly, and/or the Txakini Iya Wowapi created by First language speaker and Linguist Violet Catches-all of them unicode compliant.

Along with the technical parts of orthography, which I will discuss below, according to Dr. Mark Sebba in his book, Spelling and Society, some of the most important aspects of orthography are the social and cultural ones (Sebba, 2007). Clearly the LLC has missed the mark in regards to the cultural and social aspects of orthography. I don’t think attacking other orthographies, misleading people with half-truths, declaring their’s as the standard, and putting out propaganda is the best way to push something on free Lakxota people but this is the hand they played. As Lakxota people, we are fiercely independent. We still celebrate when our ancestors whipped the United States on Victory day- June 25. We have also had our lands taken, our ways of life banned, our children sent to residential schools, English forced on us and all of this was for our own good. But we are still here. Now we are getting a writing system and all of our data and language taken and stuffed messily into shiny products that use this orthography for our own good so we can get the privilege of buying our own language back and turning away from our elders, their writing systems, and their efforts.

Dr. Sebba speaks of orthography as being so much more than the phonetics, morphology, phonology, and technical linguistic aspects of the language (Sebba, 2007). I see different things now when I look at orthography. I see the social and cultural aspects of orthography formation. Now when I see people write with an x (Txunwin Violet’s orthography), or with Tunwin Karen’s writing system- I see resistance, I see strength, I see adaptability but I also oddly see the same stubborn resilience our ancestors had which is how we have survived as a people. I also see the conflict of our elders trying to navigate the uncomfortable terrain of turning their orality to literacy but doing it for us, the younger generations because we are so literacy focused. I see these efforts and sacrifices. I see them. I see the prayers and the struggles and the offerings. When I see the Lak̇ot̄a Iyap̄i Ok̇olak̄iċiye (often referred to as the White Hat orthography), I see a concerted effort of our people coming together to say, yes, how we write is important. I see meetings that took place in Lakota, that started with prayer, ended with prayer, had a meal in between with the customary offerings, and laughter. I see the Elders. I see teachings. I see persuasion, not coercion, and concensus building. This is how Lakota meetings go and I assume have always gone. I also see Tribal Sovereignty. I see Lakota empowerment. I see accomplishment. I see self-determination.

What do I see when I see the NLD orthography? I see assimilation, I see colonization, I see us losing who we are, I see us dancing with our eyes closed, I see overcomplication-making mountains out of mole hills, I see the trampling of Tribal Sovereignty. I see dependence, I see our data being taken under our feet, I see the exploitation of our elders (like what happened with my Grandma). How did these meetings take place when they were creating these orthographies that led to the NLD orthography? Was there prayer? Were these conversations in Lakota? Was there consensus building? Were they done with a do-gooder I know what’s best for them mentality? Did they make offerings? Maybe there were these things but it’s the feeling of not knowing and being unsure and even having to question at all that should make us all stop and think, I mean really think about what’s going on and who the authorities are or should be.

Dr. Sebba ends his book with this, “Orthographies are not simply remarkable technological achievements, though they are that. They are also complex social and cultural achievements, best viewed as sets of practices- some highly conventionalised and others relatively unconstrained. They are ‘not socially neutral exteriors of written language, but integrated parts of value clusters or systems’ (Wiggen 1986: 410). They are microcosms of language itself, where the issues of history, identity, ethnicity, culture, and politics which pervade language are also prominent. For those who are concerned about ‘standards’ and ‘standardisation’ in the face of the new technological developments like email and text-messaging, I would also emphasise that orthography, like language itself, is creative. Gunther Kress has written in his book on children’s spelling (2000:14) that in the economy of the near future ‘the identities and personal dispositions that will be most highly valued, and most essential, will be those of flexibility, creativity and innovation’. Just as we- readers, writers, speakers and scholars-celebrate the creativity, adaptability and cosmopolitan nature of orthography” (Sebba, 2007).

So to paraphrase Dr. Sebba, orthography is creative and we need flexibility, creativity, and innovation-not standardization. We need more orthography, more diversity, more innovation. Maybe more in the vein of Leroy Curley’s, A Lakota Alphabet, a system based off of the moon cycles that does not use the roman alphabet at all. Me and my wife (forgive my grammar if it's wrong but it is just English after all) are working on a minimalist system with symbols, and not letters that is based on our ways of life. I also think it would be cool to base a pictographic system off of the old winter counts or stone writings-our earliest forms of literacy.

But the LLC and their tentacles swear by their orthography and oftentimes defend it by saying it comes from Ella Deloria. To put it bluntly however, it is not Ella Deloria’s orthography. If things are changed to be “improved” upon then it is not the original work of the person. Per their video, their orthography started with Pond, then Deloria, then Buechel, then Colorado, then the Lakota Language Consortium but they say it’s pretty much Deloria. If it comes from Deloria then why not just use Deloria’s? (cue the propaganda and the violins.) I also suggest that this diacritic heavy writing system that Deloria used may have been forced on her by Boas.

On page ix of Dakota Texts, “While there, they finalized the writing system for Dakota, Boas reinforcing in Deloria’s mind the necessity of distinguishing aspirated, unaspirated, and glottalized consonants. (Boas referred to it, writing to Deloria, as “the alphabet as we designed it”; Deloria characterized it as Boas’s “new way” of writing, “for comparative study of primitive languages.”) (Deloria, 2006). By Deloria characterizing this diacritic heavy orthography as “Boas’s new way of writing” and also the fact of Boas pressuring her to distinguish aspirated, unaspirated, and glottalized consonants; it seems to be yet another instance of white folks giving their opinions and trying to tell us natives how to do things. In this case, how to write our language and what our language needs.

So anyway, back to the post. I wanted to respond to it because like I said previously, it sums up a lot of the talking points of the Lakota Language Consortium and their enablers. It can be found here:

https://www.lakotadictionary.org/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=90&t=3091 and was written by an admin by the name of nahomnikhiye-which is kinda funny and a little ironic; the admin’s name translates to something like-causes them to turn around.

It is a post in response to a user named Drew, “Drew wrote:

Hello,

Over the years I've collected various Lakota language resources with the intent of learning, and I'm interested in how you would compare yours to those of Eugene Buechel (Dictionary/Grammar book) and Albert White Hat (Reading & Writing the Lakota language). I also have the 2 book set "Lakota Tales and Texts in Translation', and a bilingual reader 'Songs and Dances of the Lakota'. I've noticed a difference in your spelling pattern compared to the others. If I start to learn using your course, will I have a difficult time reading the Lakota in these other books?

Thank you for your assistance,

Drew”

Their response, the admin nahomnikhiye, is in italics; my views are in plain writing. I am writing responses to these things because I have heard all of these things many times over but yet most of these things have been unchecked and unquestioned through the years. I think most go along with these things because the people telling us these things have advanced degrees and many have assumed only good intentions. I do not hold this same sentiment or blind faith in individuals or institutions of higher learning. I am no linguist or anthropologist however. I also have nothing to sell you. I am just a Lakxota/Dakota person, a struggling learner, parent to a little girl that we are trying to give the language to, a language teacher, and someone passionate about our language that always wants to question things and tries to find the simplest and most efficient ways of passing on our language to our children that honors our ancestors and our people.

Here is the response by nahomnikhiye on February 6th, 2012.

Nahomnikhiye: “Dear Drew,

Each of the materials you mention uses a different spelling system, yet they do not even represent all the existing spelling systems that have been used for Lakota.”This has been a problem because it inhibits the development of Lakota literacy and the Lakota language revitalization efforts.”

To start this off-this is pure conjecture, saying that the different spelling systems inhibit the development of Lakota literacy and an even bigger leap of saying that this then inhibits revitalization efforts. This is one of the foundational underpinnings inherent in this white logic and misses the most important thing- we are an oral culture. We view ourselves as an oral culture. Our language has been passed on for 41,000 years orally they say and now we are being hampered by multiple spelling systems? I would suggest we really have been inhibited and hampered by genocide and colonization but I have been wrong this whole time because apparently it has been the way our language has been spelled. This is the theme of how the LLC manipulates people. They set up the problem to give their solution in order to create dependence. The problem is that our literacy and revitalization efforts have been inhibited by different spelling systems so they then can give us their solution, their orthography (which leads to their products) in order to create dependence on their products and orthography.

But at the end of the day there is honestly no way to test this. Keep reading.

Nahomnikhiye: “For these and many other purposes the language needs a standard orthography, one that is consistently based on the sounds of the language, one where the spelling represents one-on-one matches between sounds and symbols.”

So there’s a lot to unpack but to start with, the NLD orthography is not a true one-on-on match between sounds and syllables although they push this narrative. It is a good try for formal writings but not for how our elders actually talk. One-to-one-match writing systems are referred to as “shallow” orthographies. “Deep” orthographies are like English where a letter can make a number of varied sounds. Think of the word(s) “Pacific Ocean” where the 3 c’s are all pronounced differently (Sebba, 2007). Our language has too many diphthongs and welded sounds to ever truly have a one-on-one match or shallow orthography. Diphthongs are when “a sound formed by the combination of two vowels in a single syllable, in which the sound begins as one vowel and moves toward another (as in coin, loud, and side)” (Oxford Dictionary), and welded sounds are when sounds are stuck so tightly together they make a new sound.

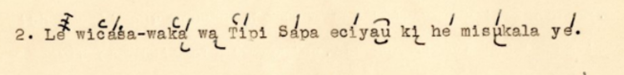

If the New Lakota Dictionary (NLD) wants to be a one-to-one match it has to account for regular speech and these diphthongs and welded sounds. An example of a diphthong is in the word “iyupte.” Speakers will make the “ai” into a dipthong that sounds like the English “I” as in “I am sick of this crap.” The NLD currently does not account for this “i” sound but speakers say this sound. Deloria wrote these diphthongs with arches above and below in some of her texts which would only add more diacritics. See the word “eciyau” (with arches) for “eciyapi-they call him.”

From Deloria, E. A Chat with Mrs. White Face, American Philosophical Society

Like above, the NLD does not account for or has not figured out how to standardize the diphthongs that come at the end of words such as “unyuhao kte= unyuhapi kte- we will have.” In some old texts they add a “w” to make this sound- unyuhaw kte or like Deloria does above, with a “u.” NLD always pushes the one-sound-to-one syllable, phonemic, or perfect shallow orthography but it leaves a lot to be desired if this is their goal.

NLD also doesn’t account for the schwa in words like mna, gla, mni. According to Dr. Redshirt in George Sword’s Warrior Narratives, “A schwa or short /e/ sound occurs between consonants when a syllable begins with bl, gl, gm, gw, and mn” (Redshirt, 2016). Deloria noted these with a period like m.na, g.la, m.ni.

Look at the word wakam.napi below.

From Deloria, E. A chat with Mrs. White Face, American Philosophical Society.

I use Deloria so much because the NLD people force Deloria down your throat although I do understand Redshirt’s critique of some of her work as appropriating George Sword’s by not giving Sword credit for his narratives (Redshirt, 2016) but if it comes from Deloria like they say their ortho does- write it like Deloria and account for things like the schwas if you are truly seeking a one-to-one match.

The “m” also does not fit their one-to-one match they are hoping for. There is the hard “m” sound like in machuwita (I am cold) but “m” is also used with an “a” as a nasal “am” sound in fast speech by elders. Instead of speakers saying the formal wanbli, many will say wambli. More examples are txahanpi- (his/her moccasins), they’ll say txahamp. This nasal “am” can also symbolize plural endings in fast speech. I’ve heard Unci say “unyam” for “unyanpi” where she would kinda swallow the “m” at the end of words like when we swallow the “m” at the end of the word “mom.”

Along with diphthongs there are letters that are stuck so tightly together that they make different sounds. I’ve heard some refer to them as “welded” sounds. In Lakota, especially in regular speech you hear this with the words “wanyanka”, or “awanyanka.” The “wanyanka” turns into “wyanka” taking on a different sound. The formal way to say “Sundance” is “Wi Wanyang Wachipi” but speakers often weld “wanyang” to “wyang” saying “Wi Wyang Wachi.” They also use these welded sounds in “awanyanka”- to look after sb, changing it from “awanyanka” to “awyanka.” I also heard my lekshi use these welded sounds with a diphthong in “wyankao kte” for “wanyankapi kte.” Good luck if you’re trying to have a one-to-one match orthography. Please forgive me for trying to explain these things in writing. This exercise shows the limits of our literacy when trying to explain our orality. More on this below.

Deep or non-rigid orthographies handle these things above very easily because they are not so rigid and structured and don’t have to try to fit into a one-to-one box. Shallow orthographies may have to admit they aren’t as shallow as they proclaim or add more diacritics to show these welded sounds or diphthongs, or just pretend that regular speech doesn’t exist like the LLC does.

I don’t know, maybe the LLC doesn't hear all the sounds of our language?

“For these and many other purposes the language needs a standard orthography” -again, this is based on a lot of assumptions. Lakota thought doesn’t operate on “standardization” and/or a heavy focus on literacy- or at least our elders don’t, and then to say that we need to standardize our literacy?!?! This seems preposterous. But if we are to standardize our literacy, shouldn’t it be one that our people have made?

We come from an oral culture (we also had sign language but this is for another time). You can see this in our stories; each a little different but with many of the same overall themes and formulas. These are facets of oral cultures. One formula I’ve found in many stories that I think that is interesting is where the characters in the story will throw a baby out of their thipi, the baby coming back in as a toddler, doing it again and then returning as a teenager, and then finally as an adult. In oral cultures these formula’s help the orator to remember the stories (also why characters are so big and there may be more violence). These are all to help the speaker remember the stories (Ong, 2013).

But anyway back to diversity, did Fallen Star’s mother dig from inside the thipi when no one was looking and fall down like in Deloria? Did she dig and open a hole in the sky and miss her family so much that she started to braid turnips and go down so far as she could then the braid broke like in Walker? Or did she fall straight through while out away from the teepee digging turnips after being told not to like in Peter Iron Shell’s telling? Each thiyoshpaye and maybe even each individual teller told the story according to what they heard or even according to their own skill and their audience which could be ever changing, this was a facet of many oral cultures-I’m not saying our ancestors did this but I’m also saying they did not not do this (Ong, 2013). We don’t know. But my question is do we need standardization? Do we need to standardize the Fallen Star stories?

What my point is is that standardization is an obsession with cultures outside of our own- we valued diversity. We still value and respect it. Go to two different sundances and you’ll see that the overall theme is there but no two are exactly the same. We value the snowflake more than the production line. This is only something that needs to be changed if you’re viewing things from outside-looking-in and not inside-looking-in. But even at that, people like Dr. Sebba (above) say orthography does not have to be standardized or put into a box. But I will say again, if we are going to standardize an orthography- standardize our literacy- which is a huge irony to many Lakota, then shouldn’t it be one lakota speakers created and not a retread narrative of something being forced on us for our own good by outsiders?

But again, back to the “necessity” of having a one-to-one match or a shallow orthography, from Sebba, Spelling and Society, page 22, “All this (research between deep and shallow orthographies) suggests that the structuralist insistence on ‘perfect’ phonemic orthographies was at best unnecessary, at worst bad science in its claim to deliver ‘learnability.’ Even if phonemic orthographies benefit learners at the early stages, mature readers may derive benefits from orthographies which have greater depth. Claims about learnability of orthographies continue to be made, however, without research to substantiate them” (Sebba, 2007).

Sebba goes on to say- “What can we conclude from all this? The ‘learnability’ question is controversial and not easily resolved because hypotheses are difficult to test: the subjects are usually children, and multiple social and cognitive factors may be involved (for example, children have different levels of reading and phonological knowledge when they arrive at school or preschool, in practice the earliest environments where testing can be carried out). To compare ‘deep’ and ‘shallow’ orthographies requires a comparison between learners of different languages, usually in different countries” (Sebba, 2007).

To conclude, there are no ways to truly test the learnability of any orthography to another because of the diversity of the learners, the young children needed for these studies. So to say that we Lakota need a one-to-one orthography is propaganda and simply in this case, another white males opinion of what we need and what our language needs. Nor is there anyone to conclude if it helps or hinders Lakota language revitalization efforts like suggested above. For me personally, I believe the LLC’s insistence on their “shallow” or “phonemic” orthography has actually hindered language revitalization because of the constant discourse and false messaging it has caused and is yet another thing from the outside pushed on us through the doors many of us young people have opened but I believe it’s time we sit back and listen to our elders. After using non-diacritic heavy orthographies-the ones that don’t mark stress and things like that, it’s tough to look at more than a sentence of writing in the NLD orthography (but again this may be more social and cultural than anything else). It’s just so busy with so much going on, it gives me headaches. I must admit, I scroll past when I see more than a couple sentences of it while scrolling on social media.

Nahomnikhiye: “The language needs to be liberated from the influence of English both in terms of spelling and structure.”

This is hilarious. Liberated from English to what…...Czech? Austrian? This is also said in the History of Lakota Orthography video I mentioned earlier. For those that don’t get this ridiculousness-these are white folks saying we need to liberate ourselves from the influence of English by the way we WRITE and also that they know how better to do this than we, you know, the Lakota people. If this isn’t saviorism, I don’t know what is? I guess it could be whitesplaining decolonization to Lakota people too though. Either way it’s messy and kinda funny.

Nahomnikhiye: “The orthography of the New Lakota Dictionary attempts to do this, it is a highly practical orthography (i.e. used for purposes of literacy) and at the same time it is consistent and linguistically sound.”

Again, it is consistent for irregular speech, written- but not for regular speech (fast speech) or how our elders actually speak, it does not account for this. The makers know that if it were to truly account for speech with consistency at a one-to-one level, the diacritics would be even more complex and elaborate than they are now like I spoke about above. But that’s often the problem, shallow-diacritic heavy orthographies “are good for linguists, but not for readers or learners.” (Sebba, 2007) Deep orthographies can handle regular speech easily because they’re not constrained by an overabundance of rules. Sebba also talks about how reading will be quicker in the long run because deep orthography readers are not reading one symbol at a time (Sebba, 2007).

I would also challenge the “highly practical” statement here. Is it truly highly practical to teach beginners a whole new writing system heavy with diacritics and stress? An alphabet and the names of more than 30-40 new letters they have to memorize? Install a new keyboard on their computer and phone? (Good luck with an apple computer by the way.) Learn that new keyboard layout? Obsess over spelling and stress while being diverted from the important stuff that will actually help them- comprehensible input and listening? How much time is wasted on this? Throwing a new language at someone while throwing diacritics, a new alphabet and the names of all those new letters, and more tech at them?

If it’s for beginners, it's adding a lot of unnecessary obstacles for them to navigate. This is hardly efficient or practical.

I also believe that focusing on “stress” raises the “output filter” that Dr. Krashen speaks of meaning when we’re so worried about everything-our pronunciation, our grammar, our stress, it freezes us and hamstrings our speech, raising levels of fear and anxiety to the point we either can’t speak or we forget all of our words and what we’re trying to say (this happens to me a lot when I’m nervous) (Krashen, 1997). Focus on communication and not trying to speak more correctly than Deloria. Not to mention the effects of historical trauma and lateral oppression in regards to our language that may make it difficult for some to speak. Lakota is stressful enough-we don’t need more stress by stressing about stress. All of this stress is making my blood pressure rise. If stress is important, note it in dictionaries like most languages do for reference, it does not need to be in the actual writing system.

But if we are worried about our speaking-stress, pronunciation, and tone, these things will get better with hearing the language more- not from texts. In our case, our orality came first. We've passed on our language for over 41,000 years orally they say and then writing systems tried to mimic our speech later. Not the other way around, we don’t try to get our speech from our writing and our pronunciation from diacritics.

Nahomnikhiye: "The dictionary and texts (and to a degree also the grammar) by Eugene Buechel use inconsistent spelling. As a result one cannot learn correct pronunciation from these materials.”

I’ve already mentioned it but we do not get correct spoken pronunciation from written materials. We get it from hearing the language, from our ear-not our eyes. (We can communicate through our eyes via writing, sign language, and gestures but we are narrowly speaking here about speech pronunciation).

If I put up Mandarin characters to someone who is not fluent in Mandarin without a speaker or knower of that language around, can we glean from the character how it’s pronounced? Can we get proper pronunciation from these materials? But we could go and ask a speaker, teacher, or learner and hear them say it-and hear them say it again and again. That’s how we can get the sounds in our heads and then we can try to say the sounds. The sounds of our language came first then people tried to mimic that in writing-not the other way around. We get our spoken pronunciation first from our ears and not our eyes.

Nahomnikhiye: “These materials have various other problems that make them unreliable. For instance the Buechel dictionary was largely based on borrowing from a much older Dakota dictionary by Stephen Riggs, and most of the borrowed entries were never checked with native speakers. Additional errors were introduced during the editing done by Father Manhardt who decided to convert Buechel's relatively consistent spelling into another orthography and he did so in such a way that resulted in unreliable and inconsistent misspelling of most of the words. Manhardt's translation of the Tales and Texts collected by Buechel is flawed, to the most part.”

They must not have been too “flawed” or “unreliable” for the LLC to digest these into their zeitgeist. They have figured these texts out, these writing systems and resources and have helped themselves to this intellectual property by incorporating these into their corpus. These misspellings are only viewed this way if you are viewing things from the outside-in, from the viewpoint of the LLC orthography in comparison to another. On another note, it's amusing that these white folks fight, argue, and criticize each other and their materials and writing systems on things concerning the Lakota people’s language.

Nahomnikhiye: "These and other things are described in detail in the introduction to the New Lakota Dictionary.

The bilingual reader 'Songs and Dances of the Lakota' is a wonderful resource, but it uses the simplistic spelling introduced by the missionaries, which means that unless one knows the language extremely well it is nearly impossible to read the text with full comprehension.

This again simply isn’t true and is someone's opinion. I can assure it is not “nearly impossible” to read because of a lack of a few diacritic marks. (By the way, this is a great resource and has recently been at the center of some controversy.) Just to touch on it again, there are studies that show that diacritic heavy orthographies make reading harder and slower in the long run. Again from Spelling and Society, p. 20, “Moving towards a deep orthography allows homophones to be distinguished while words whose pronunciation varies in context can be given a fixed representation. This latter notion has been referred to using the terms ‘unity of visual impression’ (Nida 1964: 25f) and ‘fixed word-images’ (Voorhoeve 1964: 130). Maintaining a fixed word image supports readers in developing a sight vocabulary, a set of frequently occurring words that can be recognized as a single unit without being broken down into their component letters (Bird 1999b:25) (Sebba, 2007).

So to summarize, deep orthographies like English allow you to take in more of the word at one time i.e. developing a sight vocabulary unlike shallow orthographies which may cause you to focus on smaller units and have to break down individual symbols/letters one at a time.

Nahomnikhiye: “If you learn the consistent phonemic spelling used in the New Lakota Dictionary and other LLC publications you will not only be able to learn the correct pronunciation but you will also gain better understanding of the older publications written in the inaccurate missionary spelling.”

You will learn correct pronunciation from hearing the language; our elders, but okay, they’ll keep beating this dead horse. And again, the missionaries' “inaccurate” spelling is only inaccurate to the LLC’s hopes of standardization. (I can’t believe I’m defending missionaries-makxasitomniyan, ohiyaye lo! (you win universe!)) I thought just a little while ago the writer said that these older publications are nearly impossible to read but after using their orthography they are not? This is how neo-colonization works. Colonization sets up the problem (unreadable texts) so it can then set up the solution (read using their orthography) and create dependency (you need us or else…). (For more on this and the use of trauma narratives, check out this article by Shelbi Nahwilet Meissner, The moral fabric of linguicide: un-weaving trauma narratives and dependency relationships in Indigenous language reclamation).

Nahomnikhiye: “The book by Albert White Hat (Reading & Writing the Lakota language) uses a consistent and reliable orthography (except that it does not mark word stress, an important feature of Lakota pronunciation). Anyone who learns the spelling used in the New Lakota Dictionary will have no problem reading and understanding the orthography used in Albert White Hat's book.”

Again, focusing on stress makes your stress rise, and I suggest raising your output filter. Stress being an important feature to Lakota pronunciation is again, simply one person’s opinion. Fine tuning our stress is more for the advanced learner and is not something we need to throw on beginner’s or into a writing system. Like I mentioned before, other languages note stress in dictionaries for reference, and not in their actual writing systems. On another note, not all stress is consistent. Stress can vary from individual speaker to individual speaker and from community to community, and even context to context so to try to standardize stress is more production line outside-looking-in thinking and not inside-looking-in thinking. But why must we filter a Lakota person’s book and writing system through the LLC orthography first in order to understand it? This, again, is an attempt to set up the problem (trouble reading a fluent speaker's book) to give us the solution (filtering it through their orthography) to create dependency (you need us or else….).

Nahomnikhiye: “In the past decade there has been a growing support for the new orthography in Lakota country and most schools are now using it as the standard spelling for Lakota.”

This is how LLC math works. One or a couple schools may have used their stuff around 2012 when this post was written but they’ll mislead and say “most.” They’ve been called out a number of times for giving the misleading impressions of working closely with our people.

An example with how they used Leksi Bryan Charging Cloud’s name, “Another selling strategy and method of authorization is to make it appear as if the products originate from collaboration with Lakota language experts. A tribal member and language instructor recalls that Wilhelm Meya and Jan Ullrich from the LLC had traveled through Lakota country to gather support for their orthography. He and numerous other community members and Lakota language experts complain that the LLC came only once to chat with them but their names were listed as resources in the LLC books without their approval (EI-RWB-2013). Bryan Charging Cloud, an activist in Lakota immersion and revitalization, said he did not offer any information nor did he lend support to the LLC, but his name was listed as a resource (December 14, 2012, email). Like Bryan Charging Cloud, many Lakota who had been designated by the LLC as supporters have distanced themselves from the organization and their products. With the long list of names acquired in this questionable manner, the LLC approached tribal council members and tribal education boards to get formal letters of support, giving the misleading impression they work closely with Lakota community members and gained their consensus (EI-JYS-2013). Through the list of alleged cooperators and the letters of support by tribal officials, the LLC receives plenty of financial support,” (John, 2018).

Another example of giving these misleading impressions can be found in this Lakota Journal article in 2002, Sinte Gleska University to reject Lakota Language Consortium membership (Thunder Hawk, 2002). Basically by simply having conversations with teachers at SGU, a group from Indiana University, which would become the LLC, falsely created the impression that they were working together on their grant application. SGU applied for a grant, the same grant Indiana University/LLC applied for but was rejected. “Some educators at SGU still believe their name was used to leave the impression that they supported the grant request by Indiana University. They believe they lost their bid for a grant based upon this false impression” (Thunder Hawk, 2002).

Another example is when they blasted me in an official press release on May 18, 2021. This has since been deleted but I did screenshot it. More on this in a later post but they wrote that it came from Rosebud, SD. I asked my Father-in-law, who was the President of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe at the time, about this and he responded to me in an email and assured me that their Tribal Council did not support this nor his office’s Elder’s Council and did not know where it came from.

And yet another example of giving misleading impressions to make it look like they are more community than they really are is on their website https://lakhota.org/our-role-and-impact/ where they have a memorial section to Albert White Hat (click on the link and scroll down), “Memories of Albert White Hat 2013,” where it looks like they worked together, and they supported Albert’s work. This was not true. Ask the White Hat family but also take a look at this article. https://www.lakotatimes.com/articles/dear-editor-290/ They, the LLC, set themselves up as the authority and declared their orthography as the “standard” for Lakota country trying to overthrow decades of Mr. White Hat’s work on the Lak̇ot̄a Iyap̄i Ok̇olak̄iċiye orthography. It’s interesting to note the differences in approach to orthography here from Mr. White Hat and the LLC. Instead of declaring their orthography, The Lak̇ot̄a Iyap̄i Ok̇olak̄iċiye-the group Mr. White Hat worked with, as the standard like the LLC did with theirs, White Hat wrote in Reading and Writing the Lakota Language, “if teachers wanted this particular alphabet system to become the official alphabet of their reservations, they would need to pursue its acceptance within their own tribal governments” (p. 6) (White Hat, 1999). Here is another cultural conflict, Mr. White Hat is saying, “if you want this,” he’s not forcing it on anybody and definitely not declaring the LIO orthography as the standard. He repeats this sentiment about choice again on page 10, “The orthography in this text is a suggested guide for writing Lakota sounds” (White Hat, 1999). Mr. White Hat was opposed to this group but their director, Austrian Anthropologist (Coleman, 2013), Wilhelm Meya had the audacious caucasity to give an interview on his behalf when he left (2013) and then posted it on their website. It’s still there. This is how they create the illusion that they are supported by our communities when they are not. There are a handful of people, sure, but that’s about it.

So I’m sure that a couple schools may have used their stuff in 2012 but it definitely was not “most” schools like they proclaim.

Rosebud schools did not use their orthography or products, however, there are some on Rosebud who have forgotten all that has happened and now wish to step on their own Tribal Sovereignty by writing with the orthography from the New Lakota Dictionary and by using their flawed products. Rosebud was 20 years ahead of us in relation to language/data sovereignty and protecting our language, don’t slide back now!

Currently, schools on the SouthSide of Standing Rock are no longer using any of their products or orthography. I do not know the situations in other schools but with the scare you to death to create dependence tactics mixed with the misleading impressions of working with community people, I’m sure some schools are using their stuff but it’s definitely not most like they say, and it’s only a matter of time before they see through it all too.

Nahomnikhiye: “You can also read reviews of the New Lakota Dictionary on Amazon to find out what some Lakota language learners think of it: http://www.amazon.com/New-Lakota-Dictio ... s_11561_15”

All of this to sell a book.

Chatka he miye lo.

Washicu chazhe, Ray Taken Alive emaciyab.

Ikce wichasha hemachayelo.

Lamakxota na madakota.

Txahamp Sheeca Thiyoshpaye, Kxangxi Ska Thiyoshpaye, na Aohomni Nakipxa Thiyoshpaye ematahnanyelo.

Wichoiye unkitxawapi kinhan txokatakiya takomni gluha maunnipi kte lo. Wowicala na wokunze yuha mani po.

lakotareclamationproject@gmail.com

Sources:

(2013). “Albert White Hat, preserver of Lakota Language, dies at 74.” Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/albert-white-hat-preserver-of-lakota-language-dies-at-74/2013/06/23/a05d49be-da81-11e2-9df4-895344c13c30_story.html. Accessed September 4, 2021.

Catches, V. “Txakini Iya Wowapi, Violet Catches, Lakota Orthography.” YouTube. Uploaded by Ray Taken Alive. January 18, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=StOWRp4IW4g&t=348s Accessed September 1, 2021.

Coleman, D. (2013). “Saving the Lakota Language: A Bloomington-based Initiative.” https://www.magbloom.com/2013/03/saving-the-lakota-%E2%80%A8language-a-bloomington-based-initiative/

Curley, L. “A Lakota Alphabet.” International American Indian Movement. https://internationalaim.wordpress.com/2014/10/31/lakotah-alphabet/ Accessed on September 13, 2021.

Deloria, E.C. “A Chat with Mrs. White Face.” American Philosophical Society. https://search.amphilsoc.org/collections/view?docId=ead/Mss.497.3.B63c-ead.xml

Deloria, E.C. (2006). Dakota Texts 1st Edition. Paperback. BISON BOOKS.

diphthong. Oxford Languages. https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/

John, S. (2018). Orality Overwritten: Power Relations in Textualization. http://www.sonjajohn.net/OralityOverwritten_PowerRelationsInTextualization_SonjaJohn.pdf

Accessed September 1, 2021.

John, S. (2013). “Dear Editor,.” Lakota Journal. https://www.lakotatimes.com/articles/dear-editor-290/ Accessed on September 13, 2021.

Krashen, S. (1997). A Conjecture on Accent in a Second Language. http://sdkrashen.com/content/articles/a_conjecture_on_accent_in_a_second_language.pdf

Lakota Language Consortium. “Our Role and Impact.” lakhota.org. https://lakhota.org/our-role-and-impact/

Lakota Language Consortium. (2019). “History of Lakota Orthography.” YouTube. Uploaded by the LakotaLanguageConsortium. 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TLuc9-YuuwM. Accessed September 6, 2021.

Nahomnikhiye. (Feb. 6, 2012). “Standard Orthography - a question.” https://www.lakotadictionary.org/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=90&t=3091 Accessed August 30, 2021.

Nahwilet Meissner, S. (2018) The moral fabric of linguicide: un-weaving trauma narratives and dependency relationships in Indigenous language reclamation, Journal of Global Ethics, 14:2, 266-276, DOI: 10.1080/17449626.2018.1516691

Niyake Yuza, C. (2021, January 22). Ochethi Shakowin Data Sovereignty. Lakota Language

Reclamation Project. https://lakotalanguagereclamationproject.com/blog/2021/1/22/ochethi-shakowin-data-sovereignty.

Ong. W. (2013). Orality and Literacy: 30th Anniversary Edition (New Accents) 3rd Edition, Kindle Edition. Routledge.

Paskievich. J. (1996). “If Only I Were an Indian: Becoming A Native American in the Czech Republic.” Vimeo. Uploaded by Radek Wamblisha. 2011. https://vimeo.com/24033319#t=1h55s. Accessed September 6, 2021.

Redshirt, D. (2016). George Sword’s Warrior Narratives: Compositional Process In Lakota Oral Tradition 1st Edition, Kindle Edition. University of Nebraska Press.

Rosebud Sioux Tribe Resolution No. 2012-343. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vu7p82sfGMtSwfvsfvpQFalOHrw28dSO/view Accessed September 2, 2021.

Sebba, M. (2007). Spelling and Society: The Culture and Politics of Orthography around the World 1st Edition, Kindle Edition. Cambridge University Press.

Thunder Hawk, C. (2002). Sinte Gleska University to Reject Lakota Language Consortium membership. Lakota Journal. https://calthunderhawk.tripod.com/articles/aug30-sept06/sgu_llc.html Accessed September 3, 2021.

WhiteButterfly, K. “Lakota Sounds.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1VBNtrH4-8ZOgL2FbH3q04GxkeP1TkQ_3/edit?rtpof=true&sd=true. Accessed September 8, 2021.

White Hat, A. (1999). Reading and Writing the Lakota Language. Sinte Gleska University and The University of Utah Press.